Centre researcher Deborah Goffner (red t-shirt, right) consults with her Future Sahel project team which brings toghether researchers from France, Sweden and Senegal. The aim of the project is to re-green areas across the Sahel region.

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

SRC research stories

On a mission to re-green the Sahel

A researcher's road trip on dusty roads, sleeping on floor mats and gathering data on a quest to halt desertification across the Sahel region

- The Great Green Wall is an effort to stop desertification in the Sahel region

- Halting desetification is complex and better understanding of the landscapes is needed

- Transdisciplinary research creates a multi-layered understanding of landscapes and places

On 8 February 2016, a team of six researchers including a geographer, a hydrogeomorphologist, two plant biologists, an ethnobotanist and a sociologist set off with their two drivers from Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal, to travel by truck through the diversity of dry and hot landscapes along a cartoon-like green line on the map, representing the Great Green Wall (GGW) – the collaborative effort to halt desertification and re-green areas and across the Sahel region.

The trip was the kick-off mission of the French National Research Agency (ANR) Future Sahel project in which researchers from France, Sweden and Senegal will work together with the Senegalese Green Wall Agency to further the work on the GGW in Senegal.

The expedition se off in the early morning, heading east towards the sun.

Along for the ride was centre researcher Deborah Goffner, coordinator for the Future Sahel Project, a plant biologist by background and part of the GGW and the Sahel initiative since 2011. The team drove for nine days, very rarely on-road, completely dependent on their GPS.

“We drove off with 300 litres of water, 20 kilos of onions and 300 packets of instant coffee. Prepared for a long, bumpy and very exciting road trip and hopeful about the outcomes at the end of it,” says Goffner.

“This is the other day-to-day reality of research, the one where I’m not at my desk but on dusty roads, sleeping on mats on the floor and gathering data in the field. It makes for very different workweeks than the ones I spend in Stockholm, and it’s one I wouldn’t want to be without.”

Deborah Goffner in discussions with Samba Fall in a garden in the village of Koyli Alpha.

The journey had many purposes; building relationships and trust with local stakeholders and within the team, and the scientific objective to map out the landscapes along the GGW. In Senegal, the GGW is 545 km long and extends from Potou (the most western village) to Bellé (the most eastern village), and much of it is unmapped as far as vegetation and landscape composition is concerned – the team set out to add this missing information. To do this, two methods were used:

The team took more than 1000 GPS-localized photos to reconstruct the landscape on a map.

The GPS-localised photos placed along the stretch of the exploratory mission.

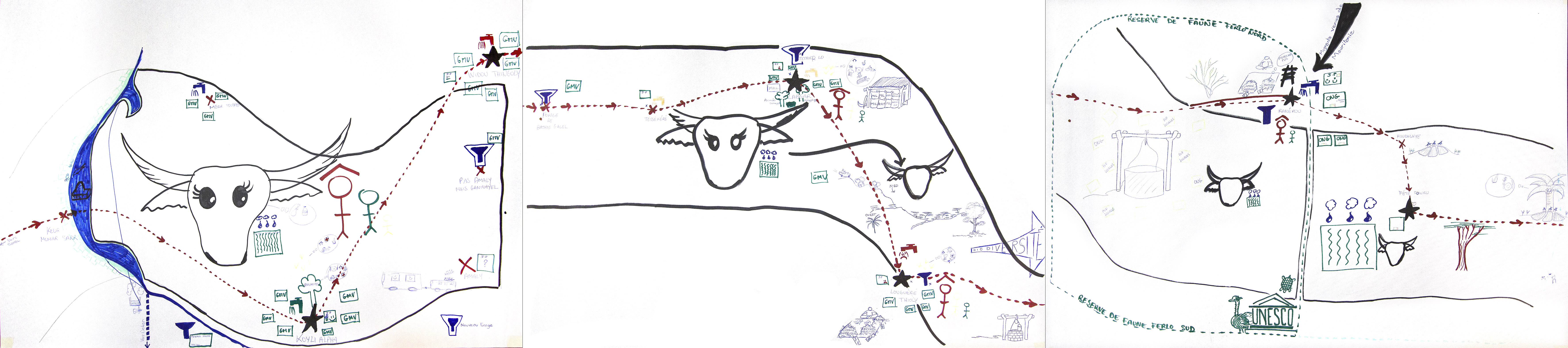

Each researcher also had a task in observing the different landscapes with respect to his/her scientific expertise (vegetation, water, geomorphology, village life, demography and social structure, etc.). At each stop along the way, the information was gathered, discussed, and illustrated on a freehand-drawn map.

“The discussions at the end of the day, drawing the map of what we had each experienced, were very rewarding. Working in a transdisciplinary team like this, sharing how you all look at things a bit differently depending on your expertise, really opens your eyes to the different aspects that should be considers and helps you experience the landscape in a different way,” Goffner says.

Top: Deborah Goffner, Margaux Mauclaire and Abdou Ka working on compiling the map after a day of travelling.

Bottom: Three examples of the maps that were produced, illustrating the location of cattle farms, water towers, wells, vegetation and on the right a UNESCO Biosphere reserve.

A second goal with the journey was to select a location to set up an additional experimental plot to test native tree species for reforestation.

“The Green Wall project was initially aimed at reforesting a wide band across the African continent and the Sahel, and while it has since been established that restoring the landscape and fighting against desertification is a more complex issue than that, and that planting trees all across the continent would probably do more harm than good, there is great potential in reforesting certain areas,” says Deborah Goffner.

“But for the replanting of trees to be successful we need to identify the good species to work with and appropriate ways of getting it to establish in the sandy soil.”

Natural stands of Balanites aegyptiaca near the village Koyli Alpha. Balanites aegyptiaca is a target species for the Future Sahel project.

In fact, along the almost 550 kilometres the team travelled through many different kinds of landscapes and land uses. While some areas were very dry and barren, others were used for agriculture or had different kinds of vegetation.

Onion fields to the West, where water is accessible in the field from wells.

A barren landscape near Louguéré Thioly.

A women-run communal fruit and vegetable gardens in Koyli Alpha. The vegetables and fruits are sold at considerably lower-than-market prices to the garden members; the excess produce is sold for profit at local markets. The resulting income earned is reinvested in a common fund for revolving micro-credits that offer women the possibility to save and invest money in a region where they typically have extremely limited access to financial capital.

The village of Ranérou was chosen as the site for the test plot based on several different criteria. Scientifically it is interesting based on its ecology and geographic location, strategically it is a good place for future work, and there was a strong local interest in hosting the test plot. Twelve different indigenous tree species, selected on the basis of ethnobotanical data, are currently being tested and planted in different ways to see what is the most successful.

Discussions in the Ranerou nursery with Moctar Bocar Sall from the Water and Forestry ministry one of the important change agents in the region.

Six months after Goffner and her colleagues set off form Dakar, the project is progressing well.

“There are many exciting results coming up in the next few months that will guide the continuation of the project,” says Goffner.

“After all, the success of the GGW will depend on its capacity to intelligently gather, generate, integrate, and use knowledge derived from a wide range of disciplines, taking into account the nature and complexity of social-ecological systems. FUTURE-SAHEL investigates on-the-ground, pragmatic resource management solutions, provides a conceptual framework to aid the decision making process within the GGW project, and with the Senegalese National Green Wall Agency as a partner, actually translates research into direct action. Beyond these solution-oriented objectives, scientific knowledge of the diverse Sahelian social-ecological systems will be produced. This exploratory mission has been eye-opening and clearly an important first step to achieving these goals!”

The Future Sahel project is funded by French National Research Agency (ANR) and brings toghether researchers from France, Sweden and Senegal

Deborah Goffner is a researcher at the centre and a research director for the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). She is based in Stockholm and at the UCAD (Cheikh Anta Diop University) campus in Dakar, Senegal. Goffner is coordinator for the Future Sahel Project.