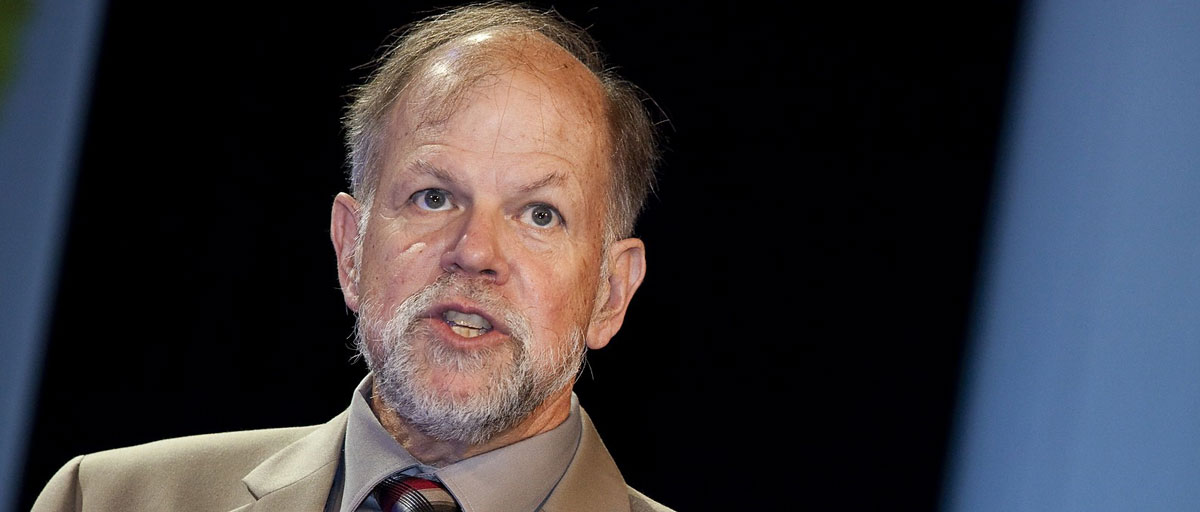

Jonas Ebbesson, director of Stockholm Environmental Law and Policy Centre at Stockholm University, is a new member of the Stockholm Resilience Centre's new International Science Advisory Council. Photo: E. Dalin/Stockholm University

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

INTRODUCING OUR SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COUNCIL

What’s law got to do with it?

Quite a lot if you ask Jonas Ebbesson, professor of environmental law and member of Stockholm Resilience Centre’s International Science Advisory Board

- The International Scientific Advisory Council (ISAC) is a body of internationally leading researchers providing strategic advice and guidance on the scientific development and direction of the Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC)

- Council member Jonas Ebbesson is the director of Stockholm Environmental Law and Policy Centre at Stockholm University and a former dean of the university’s Faculty of Law

- He believes the centre can do more to intertwine the two areas of human science and natural science

It’s good to be on the right side of the law. If you also have friends who can explain how the law works, you should be all right. Jonas Ebbesson is the director of Stockholm Environmental Law and Policy Centre at Stockholm University and a former dean of the university’s Faculty of Law.

Over the past 25 years he has lectured, written and consulted on the legal dimensions of sustainability and human rights. He has worked for a wide variety of governmental and intergovernmental bodies. In particular, since 20005 he has been working with the UNECE, where he serves as the chair of the Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee. This international Committee reviews about 50 states’ and the EU’s performance in ensuring participatory rights for the public in environmental matters.

Now, he has also become a member of Stockholm Resilience Centre’s International Science Advisory Board (ISAC), a body of internationally leading researchers providing strategic advice and guidance on the scientific development and future direction of the centre. In that capacity, Ebbesson’s advice and reflections will be priceless.

In fact, he was involved already in the creation of Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Understanding legal parts is key

Ebbesson helped write the university’s successful proposal to the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research (Mistra) to establish an internationally leading science centre on resilience and sustainable governance. In 2007 that became the Stockholm Resilience Centre with an overall funding of 198 million SEK, Mistra’s largest funding initiative to date.

Since the launch, Jonas Ebbesson has been an integral part of the centre’s development. He was also involved in the 2018 revision of the SRC statutes. As a researcher, board member and extended arm to the university leadership, Ebbesson has provided crucial perspectives on legal issues and transdisciplinary science. That will continue in his new role in ISAC.

With my background as environmental lawyer, one of my contributions will be to highlight the normative and legal issues and dimensions in the transdisciplinary endeavours at the centre.

Jonas Ebbesson

Part of that is to explain the legal dimension of international treaties such as the Paris Agreement and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

"You need to understand the legal dimension of such treaties but also other conventions relating to the environment, be it the use of natural resources or human rights. The legal impact on governments, international organisation, corporations, NGOs and individual members of the public , is crucial," he says.

An extraordinary centre with room for improvement

With new and more diverse funding replacing replacing Mistra’s original core grant (which ended in 2018), Ebbesson believes the centre is well prepared for the future.

“I think the centre has done great in the way it has approached this significant change. Stockholm University as well as serious funders for research, in Sweden and abroad, understand the value of and need for the work carried out by the SRC,” he says.

“It is an extraordinary centre for transdisciplinary environmental research, with incredible creativity and energy.”

Nevertheless, there is room for improvement, even on the most fundamental of things.

“While it has been part of its mission and work from the outset, I still it can do more to intertwine the two areas of human science and natural science in research,” Ebbesson argues. It can also get better at demonstrating how all its diverse social, political and business interaction is solidly based on science. In a period where the term “fake news” is used shamelessly, the role of science and the integrity it carries, must always be at the core of the centre’s work.

No change without fairness and legitimacy

But despite attempts to discredit experts and climate-denying political leaders, there is nevertheless a growing public acknowledgement that the planet is in a dire state. That means the role of sustainability science will be crucial for the future, but only if is based on a transdisciplinary ethos.

“As a lawyer, I see a clear role for my own discipline, but this also involves philosophers, economist, political scientists and other human scientists, all in close cooperation with our colleagues who are mainly rooted in natural science,” Ebbesson says.

Furthermore, science needs to highlight ethical aspects in contexts where some may benefit and some may adversely be affected by environmental change.

“We will never succeed in transforming society in a sustainable way unless the changes are equitable, fair and legitimate,” he warns.