Plastics pollution

The bumpy road towards a global plastics treaty

Plastic production is projected to triple by 2060. Ongoing UN negotiations aim to reach a treaty on global plastic pollution. Photo: Aryfahmed via Canva.

Plastic pollution needs to end. While most countries agree on this, negotiations for a legally binding UN plastics treaty are going slowly. Centre researcher Patricia Villarrubia-Gómez explains why.

- UN negotiations are ongoing for an international legally binding treaty to end plastic pollution

- Centre researcher Patricia Villarrubia Gómez is on-site to follow and inform discussions

- The stakes are high, but negotiations have so far been stuck in technicalities and have not been inclusive enough for scientists and affected communities

Plastics have become part of every single activity of our lives. They wrap our food, cover our electronic devices, protect us from fire, they make up most of the clothes we wear, and makeup we use.

But, just as plastics have made their way into our lives, they have made their way into every corner of the planet. Today, they impact all ecosystems. Plastics are in the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat. They have been found in human placentas, breast milk, our lungs, even in our blood. Plastic pollution is one of the world’s most pressing environmental problems, according to the UN’s environmental programme UNEP, and just last year, scientists warned that plastics have taken us outside of the safe operating space for humanity.

The Perpetual Plastic Machine – a 15-foot-tall art installation created by Benjamin von Wong. It was shown in Paris at the second round of negotiations for the plastics treaty. Photo: Benjamin von Wong.

Plastic pollution is a global problem. But despite its fundamental role in the well-being of people and our planet, there is no global legislation controlling the spread and pollution caused by plastics. At least not yet.

A plastics treaty in the making

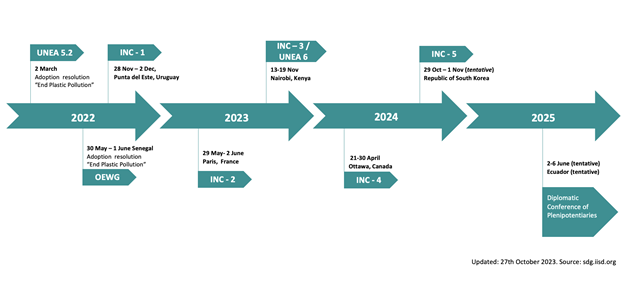

After almost a decade of discussions and resolutions, countries came together in March 2022 to close the circle on the discussions on plastics pollution, including in the marine environment. At UNEP headquarters in Nairobi, more than 175 countries agreed to enter the history books by adopting Resolution 5/14 to “End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument” — a starting point for a plastics treaty. This is the first time that a resolution includes a full life cycle approach towards plastics pollution, from production to disposal and waste management. Since then, UN negotiations on the details of the treaty are ongoing. According to the schedule, the International Negotiating Committee (INC) agreement should be reached by the end of 2024 after five negotiation sessions.

We are at a breaking point in history. This multilateral agreement could steer the path for a more safe and sustainable future by controlling one of the most widely used materials and chemicals on Earth.

Centre researcher Patricia Villarrubia Gómez

In November 2023, delegations are going to meet for the third round of negotiations in Nairobi. Centre researcher Patricia Villarrubia-Gómez will be on-site to follow and inform the discussions. She is part of the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, together with researchers from around the world, with the aim to support and communicate scientific knowledge to decision-makers and the public involved in the negotiations.

A lot is at stake in the current negotiations.

“We are at a breaking point in history. This multilateral agreement could steer the path for a more safe and sustainable future by controlling one of the most widely used materials and chemicals on Earth,” says Patricia Villarrubia Gómez.

Zoom image

Zoom imageThe negotiation process for the UN plastics treaty.

A key question of the agreement will be whether it’s able to target pollution at the source. While it’s important to clean up the millions of tons of waste that have already accumulated in the ocean, the big difference lies in whether humanity will be able to reduce plastic production and consumption, according to a recent commentary published in the journal OneEarth.

Stuck in procedural scuffles

Unfortunately, the negotiations have lately been halted by intense discussions on formalities, according to observers.

“The last round of negotiations in Paris turned into a rabbit hole of procedural scuffles based on geopolitical frictions. Discussions on the substantive matter were unfortunately blocked by this and did not proceed as much as necessary,” says Patricia Villarrubia Gómez.

Instead, tensions arose around the draft rules of procedures for voting rights, which were at least partly tainted by the shadow of the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Currently, there is only little room in the conversations for robust and independent science.

Centre researcher Patricia Villarrubia Gómez

All comes down to whether a treaty should require a consensus among all countries or whether a two-thirds majority should be sufficient to sign an agreement. While most countries favor the second option, a few powerful actors such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, Brazil, Argentina, India, China, and the US advocate for a consensus solution. This would give any country the right to veto parts of or the whole treaty — and result in a much weaker agreement.

“While decisions about the rules of procedure are important, these discussions occupied half of the second round of negotiations. Some delegates saw this as a strategy to block any progress, and some even lost their patience. A delegate from Senegal took the floor stating that ‘consensus is what kills democracy’, explains Patricia Villarrubia Gómez.

Not all voices are heard yet

Another matter of concern so far is participation and access to the negotiation process. The second round was marked by the limited capacity of the UNESCO building, which served as the venue, and allowed only 1,500 delegates, leaving out more than 1,000 already accredited participants. The choice of venue excluded the voices of some of the communities that are most impacted by plastics pollution, especially those in the Global South including waste pickers and representatives from indigenous communities.

In contrast, lobbyists from among others the oil and plastic industries have a significant presence in the negotiations.

Centre researcher Patricia Villarrubia Gómez

Participation is also an issue for scientists.

“Currently, there is only little room in the conversations for robust and independent science,” says Patricia Villarrubia Gómez.

Like in all UN-led multilateral agreements, public universities face multiple barriers to getting accredited as observers. In theory, government-funded universities cannot be accredited according to UN rules, as they are assumed to represent their respective country. Practically, that means that most independent scientists rely on being invited by other already accredited organizations, which makes scientists heavily under-represented in global policy negotiations.

“In contrast, lobbyists from among others the oil and plastic industries have a significant presence in the negotiations. For the second round in Paris, more than 190 industry representatives were on-site,” says Patricia Villarrubia-Gómez.

As a result of the Scientists’ coalition the issue of ongoing silencing of and harassment of scientists has made it onto the agenda of Volker Türk, the United Nations high commissioner for human rights.

When it comes to the content of the agreement, there is still a long way to go. Since the last negotiations, a first draft text, a so-called ‘zero draft’, has been published.

“The zero draft is of course a step forward. But important aspects such as clear definitions of plastics or plastics pollution, or what represents a full life cycle are missing. An independent science-policy panel would really help with this and needs to be formed. Issues of Human rights and indigenous and traditional knowledge are also still absent which prevents this from becoming a strong and solid agreement,” says Patricia Villarrubia Gómez.